Denmark: Siltanews – News Desk

Data analyst Kelly Draper Rasmussen highlights that Denmark sees peaks in international migration during early childhood and high school years. However, with only one international education option, many families are forced to leave to secure different opportunities for their children.

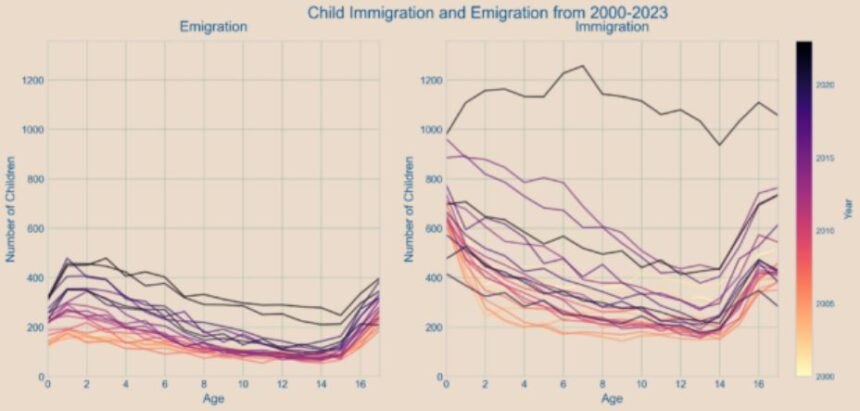

Denmark’s international workforce follows distinct patterns when moving with their children. Data show two clear peaks in both immigration and emigration: one during early childhood (including babies who “immigrate” by being born here) and another during the high school years. Between ages 6 and 14, international families are more stable in their residence. These patterns have remained remarkably consistent over at least the past two decades, suggesting structural causes.

If students are fluent in Danish, there are a range of choices after primary school in Denmark: all sorts of vocational, academic, and technical courses preparing for university. For a young person whose school language is English, there is currently one choice: the International Baccalaureate.

The International Baccalaureate Diploma Program was started in the 1960s to cater to a new population of children whose parents worked abroad. The aim was to prepare learners to be ready for university when their families returned to their home country.

The Diploma Program is regularly benchmarked against other college preparation programs across the world, so that students can attend university worldwide if they choose. This makes it a rigorous and challenging experience for the students. In addition to six academic subjects, they are also required to study epistemology, conduct extended original research, and complete projects in community service, creativity, and “activity” (such as rock climbing or sports).

This ambitious program is not for everyone. Not all adolescents are ready for the time management nor the academic standards required. This can leave international families with no option but to move to a country where their child can complete secondary education in a school that matches their needs and skills.

For a country like Denmark, it is a big loss to have international families leave. It makes much more economic sense to retain international workers long-term since companies do not need to recruit, move, and onboard new workers. Denmark has been losing workers at this life stage consistently for at least 20 years.

Having young people educated in such a way that they can find their place in adult life in Denmark and be prepared for professional life, even if they are not particularly academic, will be such a boon for both those students and for Denmark in general.